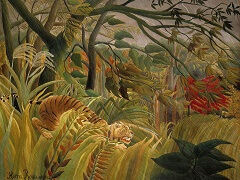

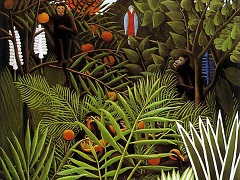

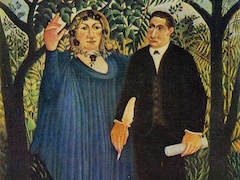

The Equatorial Jungle, 1909 by Henri Rousseau

It is significant that an obscure inspector of customs should have changed the course of painting in our time almost as much as Michelangelo or Caravaggio did in theirs. None of the Post-Impressionists, with the possible exception of Vincent van Gogh, influenced the direction of the modern French School to the same degree as did the self-taught Rousseau. His admirers and disciples included most of the leading artists of the first quarter of the twentieth century: Picasso, Braque, Derain, de Chirico, Vlaminck, to mention a few.

For Rousseau brought to painting the qualities that these artists admired: directness of vision, the innocence of technique, and naivete of spirit. He was one of the very few unself-conscious painters of modern times. When a critic was preparing a Who's Who of French artists, Rousseau appeared with his self-portrait and his biography. Speaking of himself, he said:

He has perfected himself more and more in the original manner which he adopted and he is in the process of becoming one of our best realist painters. As a characteristic mark, he wears a bushy beard."

It is surprising to find that Rousseau considered his paintings realistic, but we know from many sources that he wished to render nature accurately and that he envied the academic painters their greater skill. But still more important than realism to his mind was the artist's emotional response to his vision. Apollinaire, the French poet, describes how the douanier when painting a terrifying subject, would quite genuinely become frightened by his own creation and rush trembling to open a window. His pictures had for him a life of their own. He once said that he did not mind sleeping in his uncomfortable studio, for, as he put it, "You know when I wake up, I can smile at my canvases." And it is this curious inner life which makes The Equatorial Jungle, which he painted in 1909, the year before his death, so fascinating a picture. The wilderness Rousseau depicts is over fecund and sinister. Leaves and flowers are magnified even beyond the fantastic fertility of the tropics. Interwoven and interlocking, they form a barrier and convey a sense of the impenetrability of the jungle. Within this jungle and furtively peering out is a hidden life, menacing and full of small sounds. The rhythmic beauty of the repeated leaf shapes in Rousseau's landscape is extraordinary, and as a decorator, he is difficult to surpass; but the real wonder of the painting lies in its imaginative realism, in its powerful conception, in the degree to which the artist is possessed by his subject until the scene he depicts comes alive in a strange, almost magical way.